Until recently, library time at Belpre Elementary School wasn’t a hit with students. Reading, or being read to, and working on keyboard skills didn’t inspire great interest. Some students even tried to avoid this “special.” So Rebecca “Becci” Hartline, library media specialist at this southeastern Ohio school, rethought the whole approach.

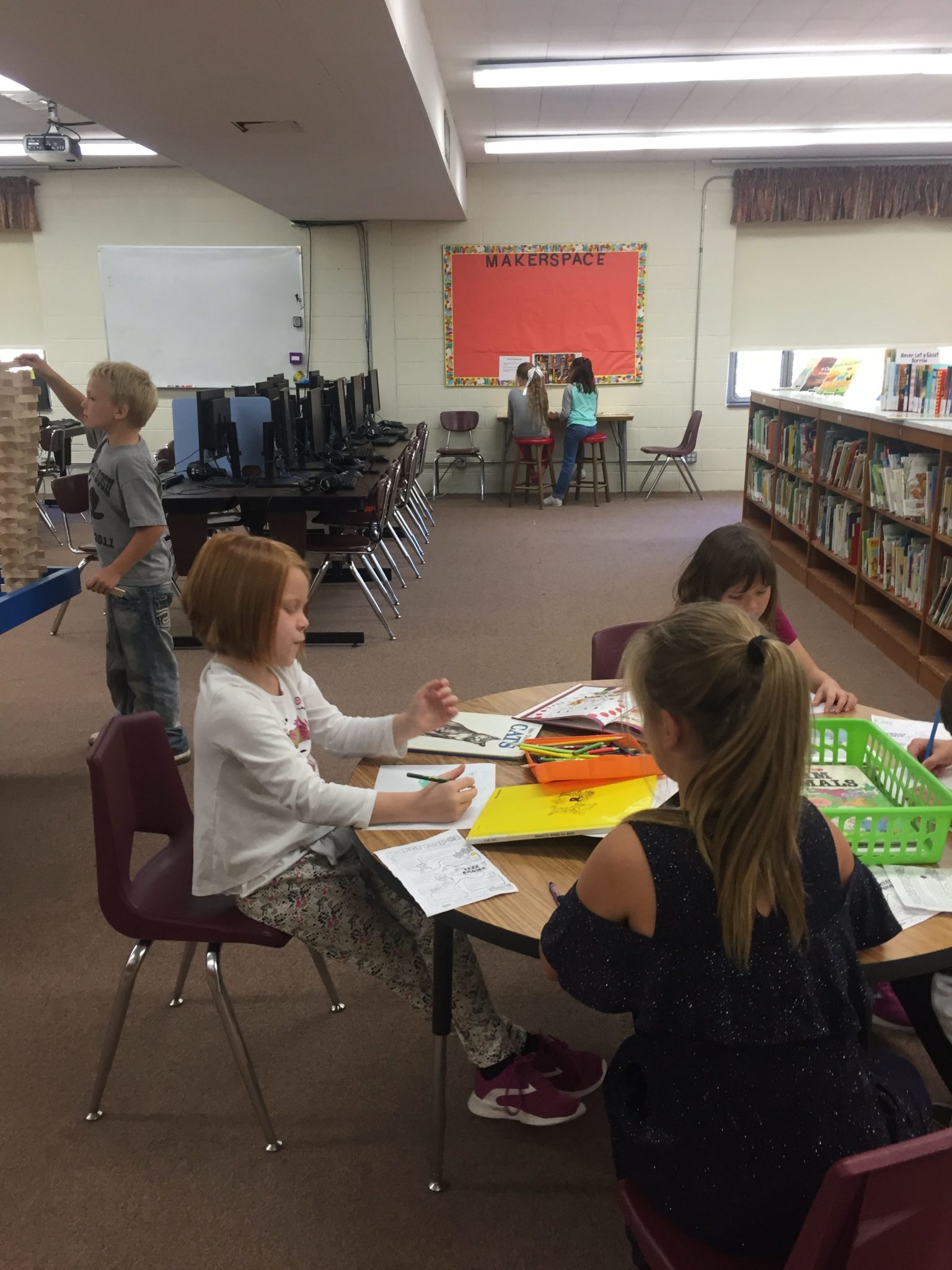

After doing research, and with the input of fellow educators and community members, she created a makerspace inside the library, offering a variety of STEM-based learning opportunities that actively involved and challenged students. “The makerspace has changed the students’ attitudes,” Hartline said. Her outstanding efforts to improve educational opportunities at the Washington County school have earned Hartline the Ohio STEM Learning Network’s Excellence in STEM Teaching Award.

How did she transform the library, and what non-traditional activities does it offer? Read on for all the details:

Q: Tell us about your school.

A: Belpre Elementary School is a K-6 building. There are about 65 to 85 students per grade level. Grades 4-6 are departmentalized, grade 3 is partially departmentalized, and grades K-2 are self-contained. Students have a different “special” each day with a rotation schedule for Fridays.

Belpre City Schools has been working on a “Portrait of a Graduate” initiative in which groups of teachers along with community members have developed a set of competencies they think are essential for our graduates to master to be successful. Within that initiative is the project-based learning model. I am a member of that effort. The makerspace foundation of “create, construct, collaborate and communicate” are essential skills our students must develop to meet these goals.

Belpre City Schools has been working on a “Portrait of a Graduate” initiative in which groups of teachers along with community members have developed a set of competencies they think are essential for our graduates to master to be successful. Within that initiative is the project-based learning model. I am a member of that effort. The makerspace foundation of “create, construct, collaborate and communicate” are essential skills our students must develop to meet these goals.

Q: What inspired you to revamp the school library into a makerspace? How did you do this, and who assisted? How was the makerspace funded?

A: In the 2018-19 school year, I was assigned to the library, where I did traditional library and technology lessons, read books to students, checked out books and basically used up the 45 minutes I had with all 540 students per week. Feeling that I was wasting 45 minutes of precious learning time with my students, I started searching for ideas.

First an article, then a book, then another book, which led to conversations with my colleagues, and I decided the worst thing that could happen is that administrators would say no. As luck would have it, one day our superintendent came into my office and asked what I would like to do next year. Without hesitation, I pitched the makerspace idea, and he agreed to let me try.

I contacted eight folks – a special education teacher, kindergarten teacher, occupational therapist, PTO president, district librarian, coding club coach and two community members/parents – who agreed to be onboard for a committee. We met in July 2019, created a budget and made a plan. I wrote one crowd-funding grant application, received a small donation from the PTO, my son built tables and the district covered the rest of the costs. I started using the makerspace on the first day of school in fall 2019.

Q: Describe what is available to students in the makerspace. How are these new opportunities integrated into the traditional library offerings?

A: The makerspace has eight horizontal work spaces (tables) and four vertical workstations (wall-mounted spaces). We have a Scrabble wall, LEGO wall, magnetic whiteboard and a peel-and-stick ruler. There are four tables, each made of a 4×8 sheet of plywood with a 2×4 turned-on edge as a border and mounted on sawhorse-style legs about 24 inches off the floor. The tables were inspired by the First LEGO table design directions. I found some random tables for the jigsaw puzzles and plan to build one more table because the plywood tables work so well.

|

|

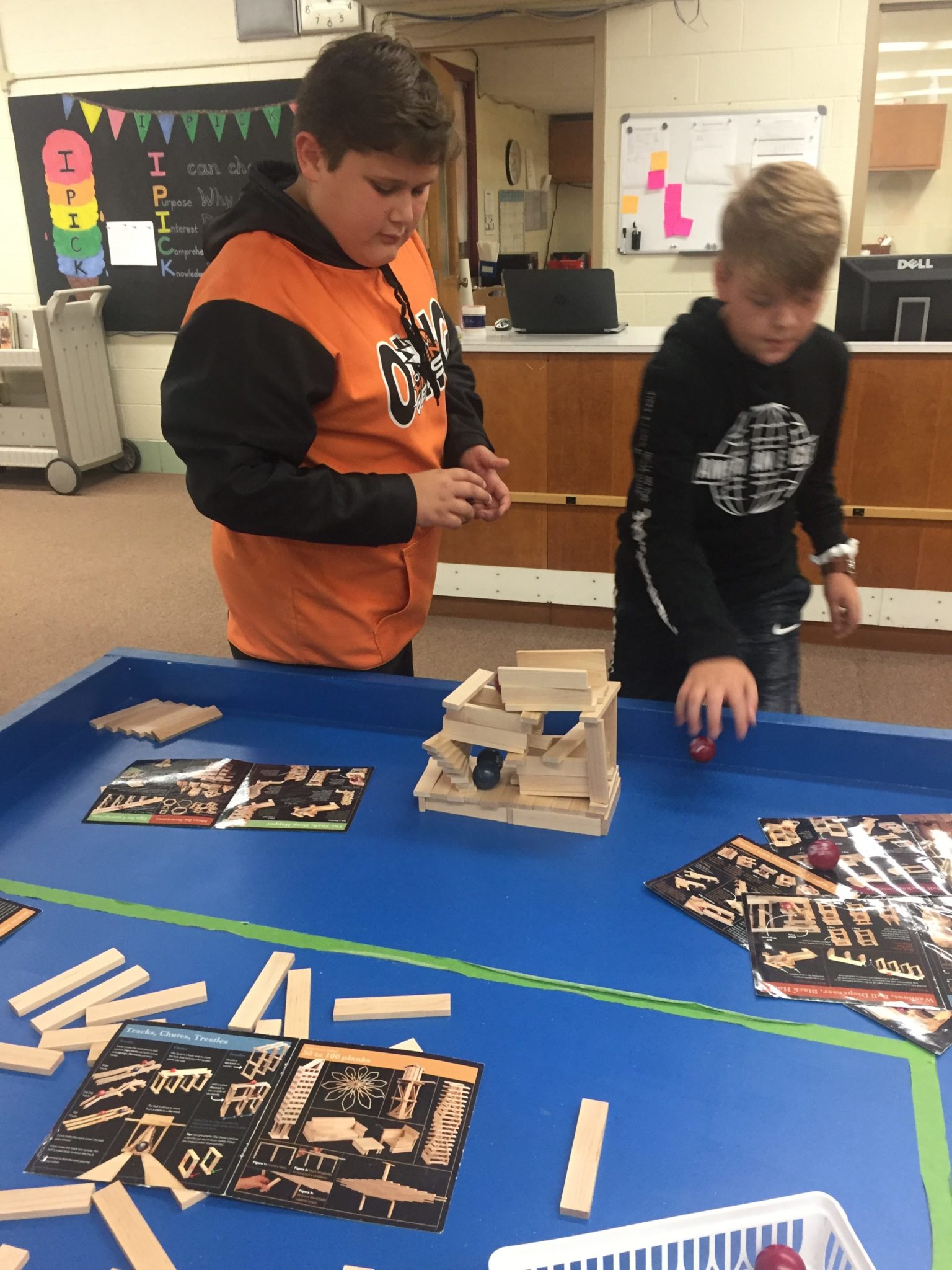

There is a LEGO table, KEVA Planks table, Strawbees table and robot table. There is a puzzle table and an art table. Two tables change activities among games, art, gears and magnets.

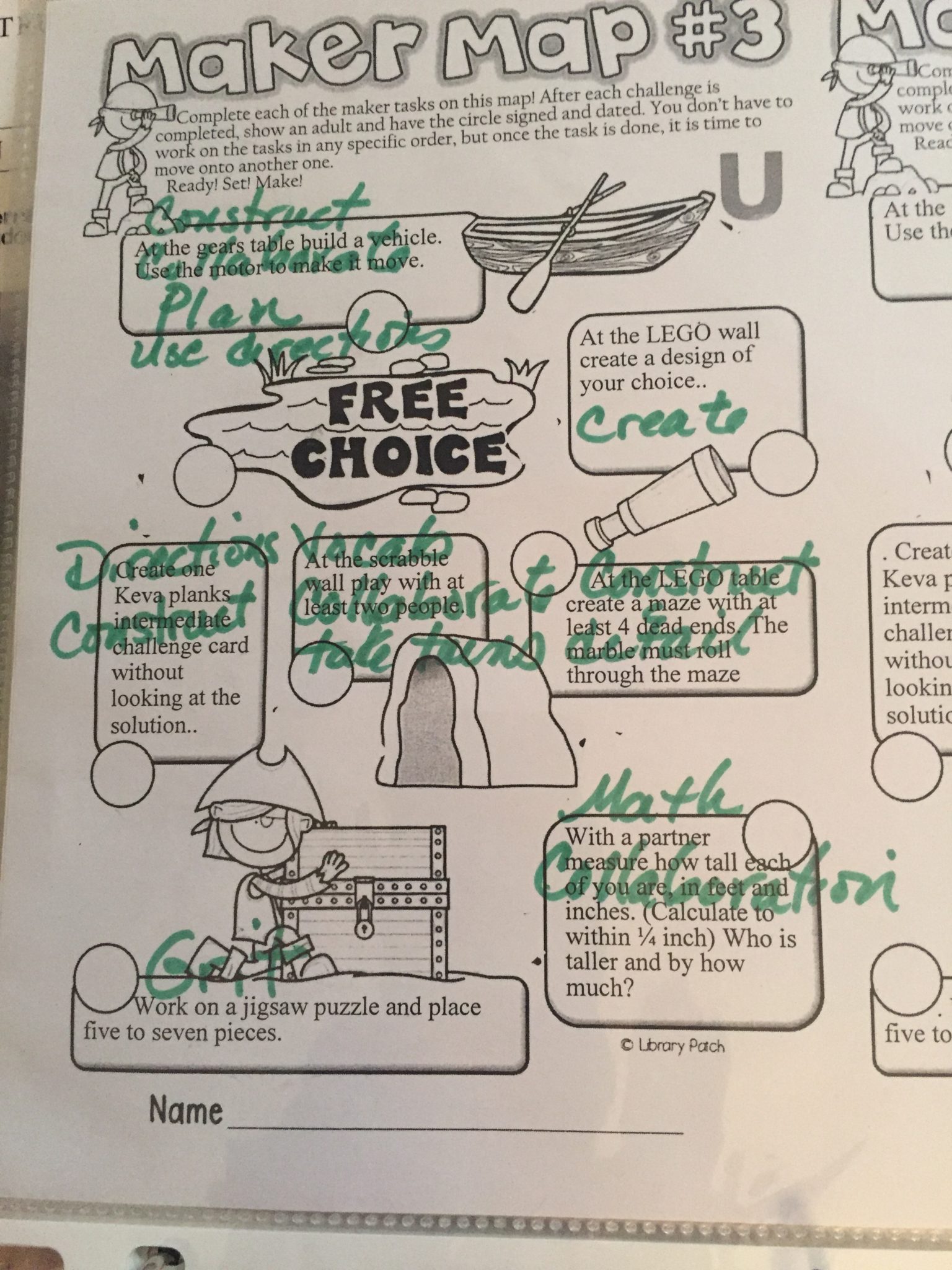

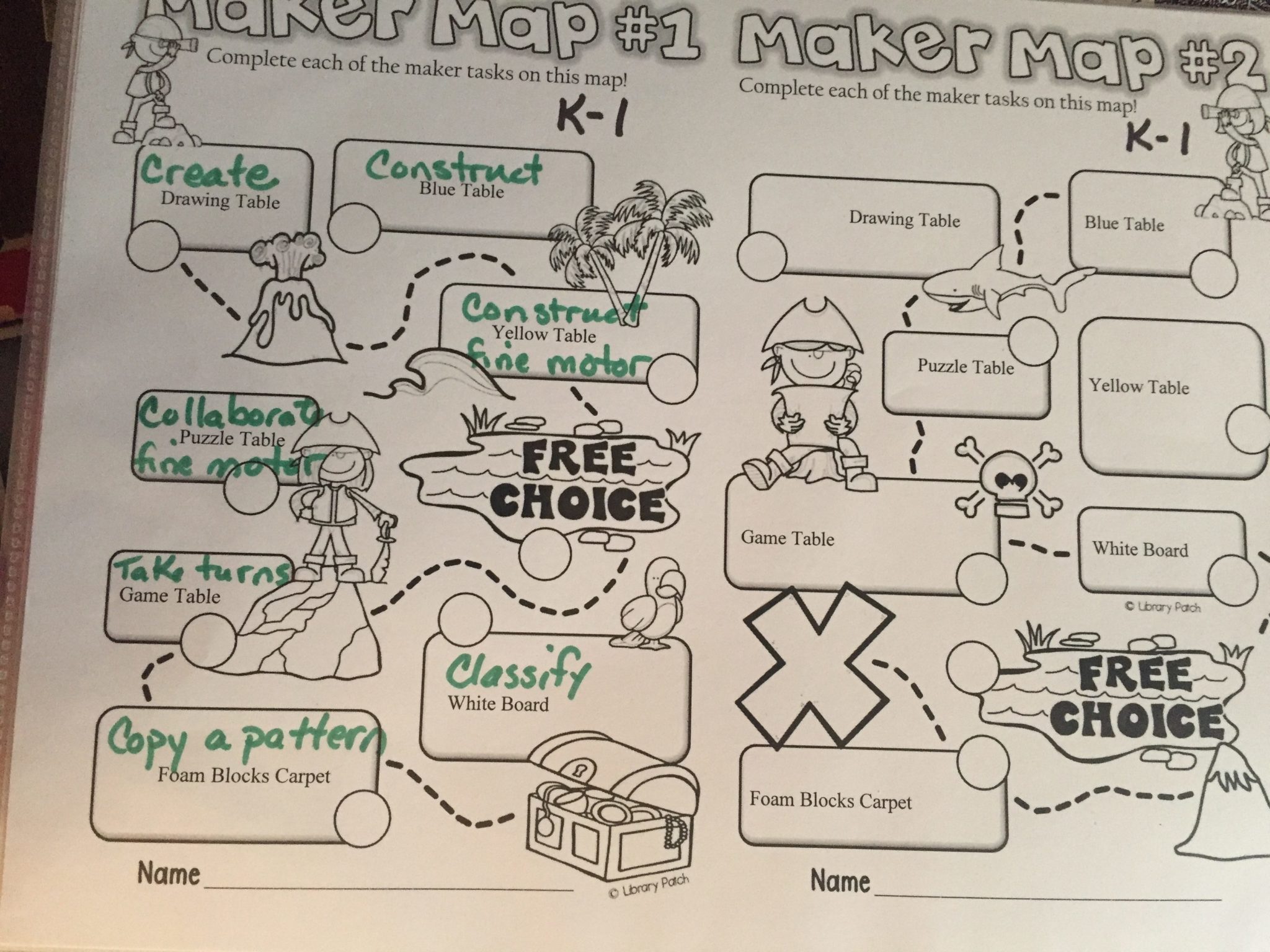

I started with a plan to include the four C’s (create, construct, collaborate and communicate) and put those activities on a map, which each student uses to guide his or her progression through the makerspace. (I got the map template from Teachers Pay Teachers). Then I made two rules: walk, and use an inside voice. Violators of the rules get a 5-minute timeout from the makerspace. It is remarkably effective.

As each student completes a makerspace challenge, he or she must get my initials on the map before moving on to another challenge. The students don’t always complete a challenge in one class period. For instance, a challenge might say that the student must place at least five pieces into the jigsaw puzzle. “At least” means that the student can choose to spend a whole class period working on the puzzle.

Some students might struggle with the task and be dishonest about the number of pieces placed. It can be an opportunity to talk about grit and honesty or character and self-awareness.

At first, I tried to create challenges that would incorporate the standards being taught in the classrooms in the different grade levels, but that proved difficult because of scheduling. I see the students once per week for 45 minutes, and in the three quarters that we were in the school building during the last academic year, most students had not completed three maps.

When the students come into the library, they first walk to a computer and log in to Typing Agent, a program that teaches keyboarding and digital citizenship. When everyone is logged into the program, I start the timer for 10 minutes. When the timer rings, the students come to the counter, pick up their maps and start tackling challenges in the makerspace. I set another timer for turning in maps at the end of the period.

Any student who wants to check out a book brings it and his or her library card to the counter and self-checks out with the scanner. Circulation in my K-6 library is about 1,200-plus books per month.

Q: How has the makerspace made a difference in education at your school?

A: The makerspace has changed the students’ attitudes. Unfortunately, their library “special” had been dreaded and avoided when possible. It was not considered “fun.” The STEM learning tools in the space, however, changed the whole atmosphere. The students still practice keyboarding, learn the Dewey library system, check out books and learn essential digital citizenship skills. The difference is, when you put a few things in the space that spark curiosity, and students are engaged in a natural way to figure out how things work, they don’t stop trying.

A: The makerspace has changed the students’ attitudes. Unfortunately, their library “special” had been dreaded and avoided when possible. It was not considered “fun.” The STEM learning tools in the space, however, changed the whole atmosphere. The students still practice keyboarding, learn the Dewey library system, check out books and learn essential digital citizenship skills. The difference is, when you put a few things in the space that spark curiosity, and students are engaged in a natural way to figure out how things work, they don’t stop trying.

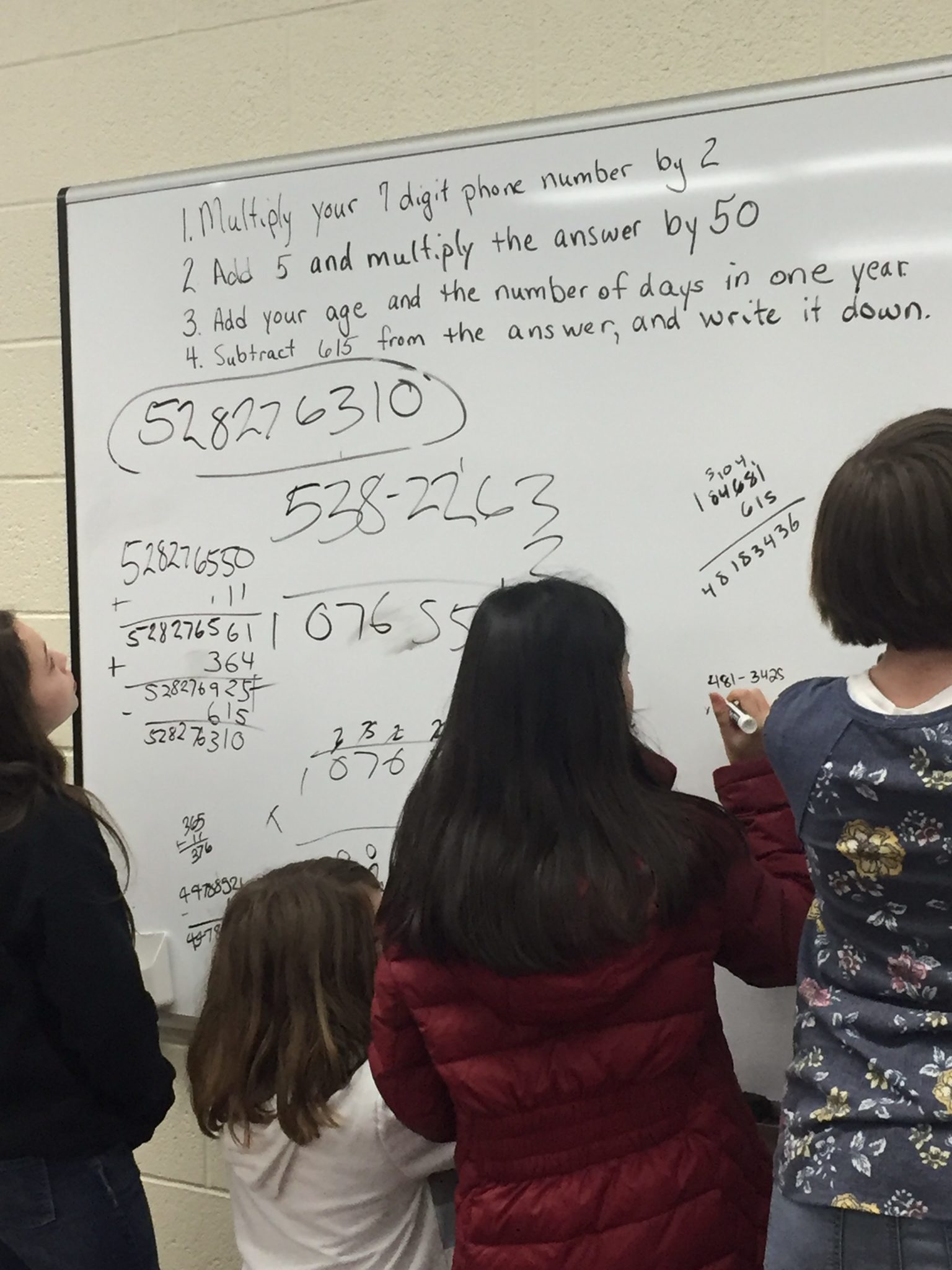

The STEM tools lend themselves to this natural curiosity and learning in children. Our math teachers talked about how some children just don’t understand measurement. So I put a standard measuring tape up on the wall with this challenge: “With a friend, measure how tall you are in feet and inches (to ¼ of an inch), and how tall your friend is, and determine who is taller and by how much.” The tape measure is next to a white board where the students can work it out.

One of the LEGO challenges is to build a rocket launcher and test the student’s rocket against someone else’s, determining whose would go farther and by how much. Students can use standard or metric measurements.

The examples go on and on. The key is to be mindful of the skills needed and keep the challenges engaging and rigorous, even if they are simple.

In the six months that I offered the makerspace during the past school year, I saw no student get overly frustrated. They just kept trying. One sixth-grade girl said, “Mrs. Hartline, I don’t like this makerspace.” I asked her why, and she said, “You have to think too much,” and then she smiled and went on. That is when I knew I had found what we as educators are looking for.

Q: How does your school try to foster the STEM for All concept?

A: Because I see every student in the building, the opportunity is there for all of them to be exposed to the makerspace. The maps include a “free choice space,” so the students must return to one of the stations, doing the same challenge or taking it a bit further. So if a student loved the Scrabble wall, he or she may choose to get a game going and play just for fun, or the student may choose to use free choice to help a friend complete a task.

Some students choose to build something because they thought of something to add to a design or just wanted to create something else. Some students choose to work at the jigsaw puzzle just because they like to see more pieces put into the collaborative project.

One unexpected development – of which there are many – is that our speech therapist approached me regarding a summer speech camp in the library makerspace. When the virus shut that down, she talked about adjusting the schedule so she could meet with her speech groups in the makerspace. The occupational therapist is interested as well. Those students who need help with fine motor skills improve significantly in the makerspace.

There is a lot to be said for the horizontal and vertical spaces. There is something going on when young students switch from a horizontal plane to a vertical one. Some can do it smoothly, without effort, and some must work significantly harder. The point is, they do it, and, if it is difficult, they keep trying. I don’t rush them, test them or correct them. They just learn.

Q: If schools are open to students in the fall, how will you use the makerspace? Do you plan any changes or upgrades? If education is still online, how will you contribute via computer?

A: I had some changes that I was going to make if we are open and free of the virus. I plan to move the hydraulics unit to the high school library so the seventh-graders will have access.

There are makerspace challenges online. One is to log in to Scratch and create an animation and share it. Another is to login to Typing Agent and play a game with a friend, but one friend has to be in the minilab and one in the library so their communication must be online.

Unfortunately, I have not decided how the makerspace could work this year with the rules for disinfecting. If I figure out how that can be safely done, I will open at least some stations. Right now, just using the computers is a huge challenge because we are not yet a 1:1 school for technology. In fact, we are hundreds of Chromebooks away from that goal.

|

|

|

Q: What advice would you give other educators who might want to build a similar makerspace in their school?

A: I don’t think any two makerspaces could possibly be alike. The whole point is to create a space in which your stud ents participate and engage in their own learning. The students guide what you put in or take out of the space.

My students learned to collaborate while putting together a 750-piece jigsaw puzzle of the rainforest, but when I put out a set of gears and directions for building a windmill, they struggled. Another example: When given foam blocks and asked to repeat the pattern of blocks in our walls, almost none of the students could do it.

For these activities, I am the one doing the learning. I must change the instructions until the students understand.